After a long delay, partially a result of the global COVID-19 pandemic, we’re back! This post is written by guest blogger Shealyn Golden, a curatorial assistant in the Ethnology & History department. Shealyn recently installed an exhibit of historical medical supplies on the 4th floor at the UAF Rasmuson Library.

The history of medicine can be thought of in many different ways. Wacky, primitive, askew, deceptive, and dangerous are all words that have been applied to historical medical practices. However, the sentiment these words imply is often reductive and misses the truth. While there have been many “snake oil salesmen” and medical practices based on incorrect thought processes throughout history, most medical practitioners were genuinely trying their best. Unfortunately, they lacked the scientific understanding and necessary equipment to practice evidence based medicine, which is the gold standard for modern biomedical techniques (aka “Western medicine”). In the absence of modern gold-standard practices, medical practitioners largely relied on the assumption that anything that provoked a noticeable effect had medicinal qualities; these were generally emetics, laxatives, diuretics, and anything that could cause an altered state of mind.

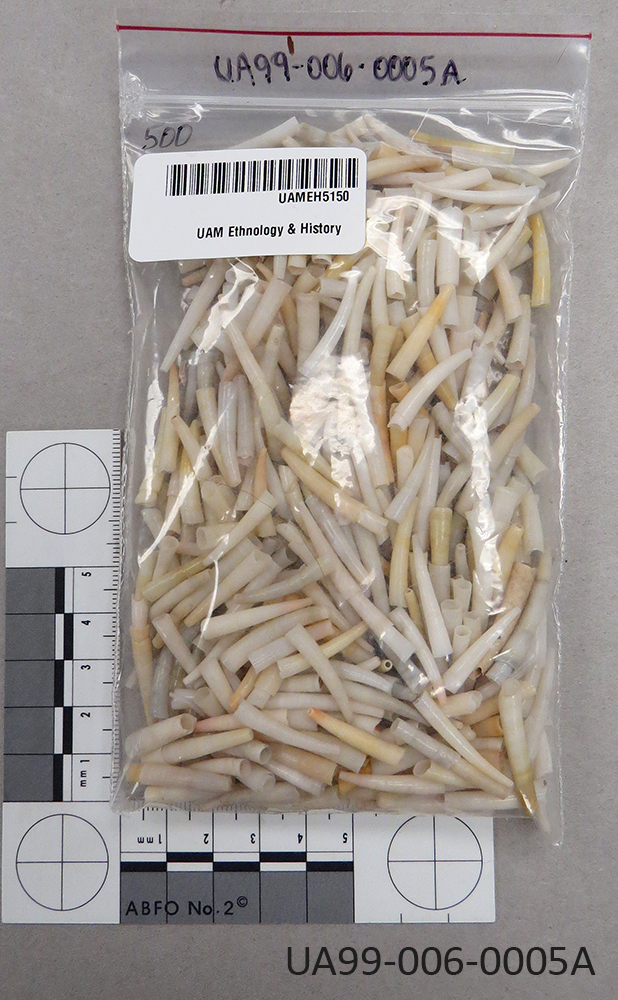

The collection of Western health care objects at the University of Alaska Museum of the North showcases health care practices over roughly a 150-year period. The earliest pieces in the collection date to the 1880’s while the most recent were collected in the last few years as part of the COVID-19 project. Like the majority of the collection in the Ethnology and History Department, the objects in the health care collection were collected in Alaska and Northern Canada.

The museum’s collection also has items related to Indigenous health care practices. These practices and perspectives are beyond the scope of this post. If you are interested in Alaska Native concepts of health and wellness, please visit the website for the Center for Alaska Native Health Research.

The earliest objects in the health care collection likely came north as part of the Alaskan Gold Rush, which lasted from approximately 1887 to 1914 and had two main “waves,” one to the Klondike area and a second to the areas north of Nome. Although the Klondike is actually in Canada, it is still considered by many to be part of the Alaskan Gold Rush for three main reasons: first, some of the earliest miners to head to the Klondike were residents of Circle City, Alaska; second, of the most-used routes to the Klondike area, three went partially through Alaska, bolstering the economy in the areas along the route; and third, the Klondike Gold Rush was responsible for the beginning of the population boom that concluded after the rush to Nome. Like gold rushes in other areas, people got word that gold could be found in the Klondike, and later Nome, and flocked to the area to seek out their fortunes. But moving into arctic and subarctic climates can be both difficult and dangerous, and the majority of people who came north were both ill-prepared and ill-equipped.

While mining out in the wilderness, individuals and small groups needed to be able to tend to their own health care. Today, even with the advantage of modern communication and transportation technology, Emergency Medical Services in Alaska and Canada can take multiple hours to get to their patients simply due to how remote their patients sometimes are. Modern hikers and backpackers often have extensive first aid kits, in case they need to hold themselves over until they can get professional medical help.

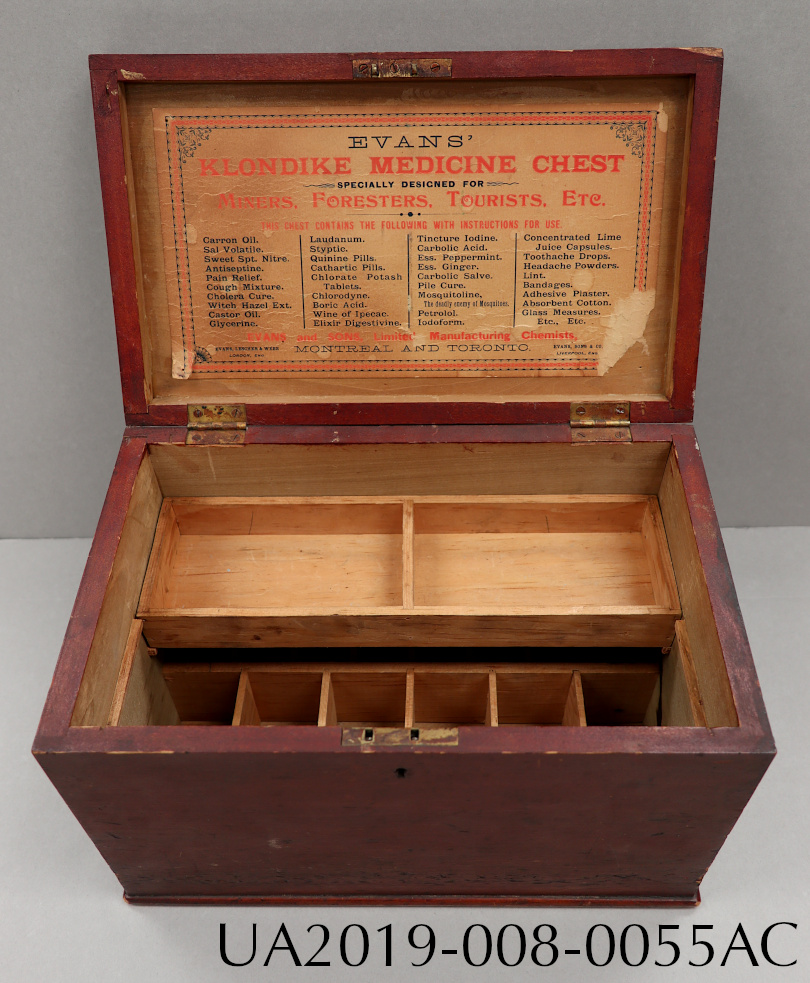

To make it easier for people heading into the Klondike to outfit themselves, many “druggists” made their own Klondike Medicine Chests. These chests were filled with all of the medical equipment and medicinal supplies considered necessary for miners, trappers, tourists, and anyone else going into areas where they would be responsible for their own medical needs. Like most medicine chests, the Klondike Medicine Chest was stocked mostly with painkillers (primarily cannabis and different formulations of opium) and sundry laxatives. By the 1880s the value of antiseptics was more widely accepted in the medical community, so various antiseptics (ostensibly for different applications) were also included, as well as items for packing and covering injuries.

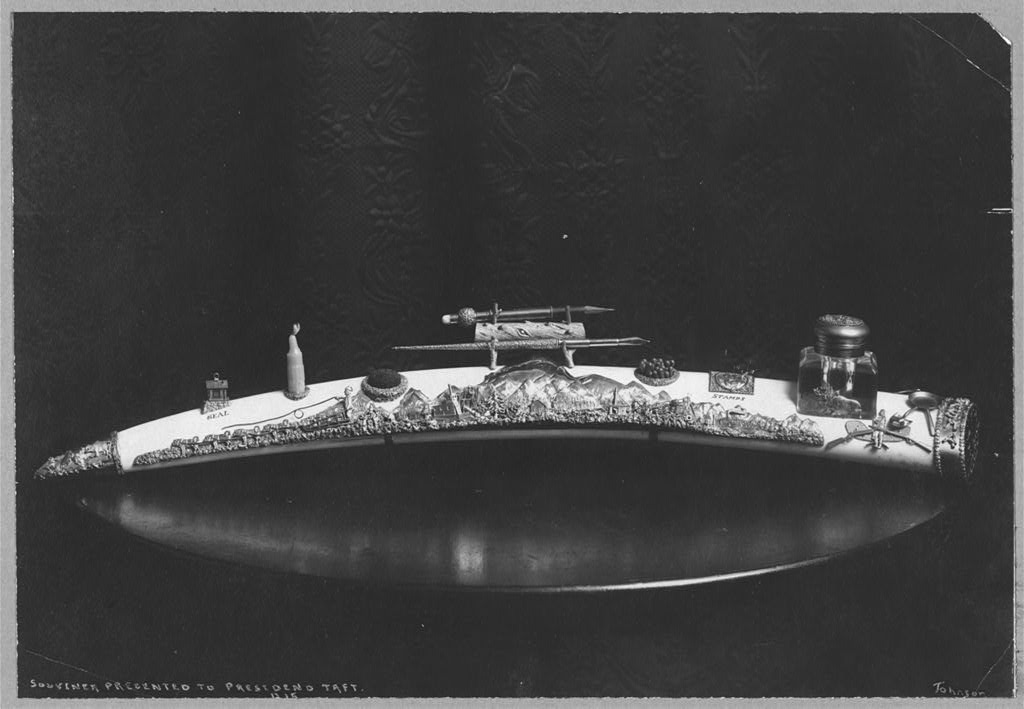

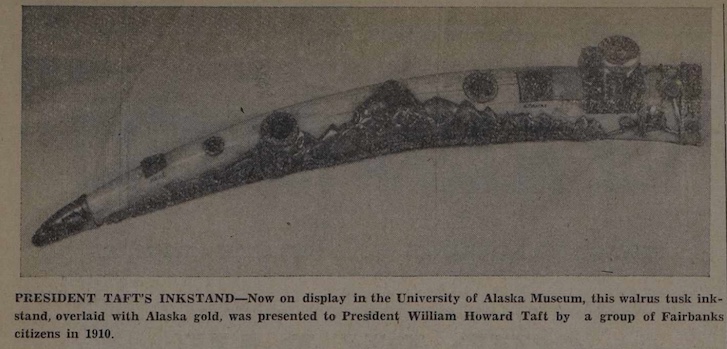

This Klondike Medicine Chest was made by Evans and Sons Limited, likely in Canada between 1889-1906. This chest was originally filled with the items listed in the inventory, which were, unfortunately, missing upon donation. However, many of the individual pieces have a counterpart in the museum collection. View this spreadsheet for the original inventory and comparable items in our collection.

Many modern cities in Alaska were founded and/or experienced a population boom due to the search for gold. Fairbanks is one such city, where a permanent settlement was founded in 1902 after gold was discovered by Italian immigrant Felix Pedro, né Felice Pedroni. As the population grew, support services for the new residents also moved in. Homes, schools, churches, banks, saloons, a library, a hospital, and various shops and markets were all established within a decade of the gold strike.

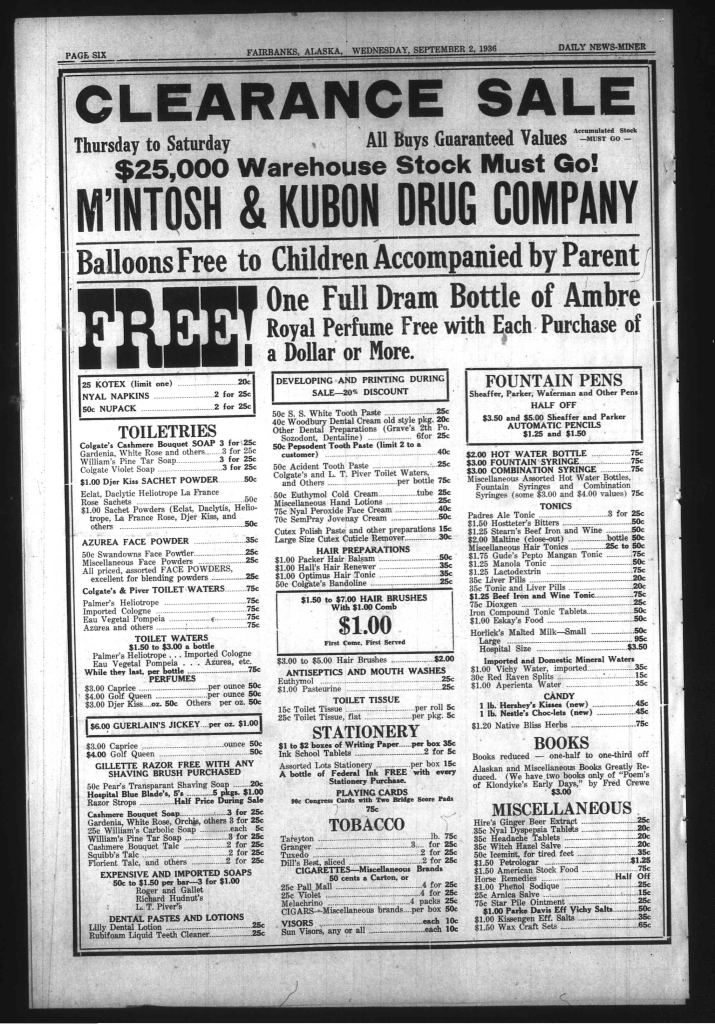

One of the shops that was opened was the drug store of McIntosh and Kubon. John McIntosh (the UA Regent for whom McIntosh Hall on the UAF campus is named) came to Fairbanks in 1904 after having been in the Klondike (specifically Dawson) for eight years. While in Dawson, McIntosh had worked with Ralph Kubon, and in 1909 the two opened McIntosh and Kubon in Fairbanks. At McIntosh and Kubon, and the other pharmacies that were opened in Fairbanks, people could purchase the various medical items they needed for home use, as well as other sundries such as safety pins, tobacco, razors, and toiletries.

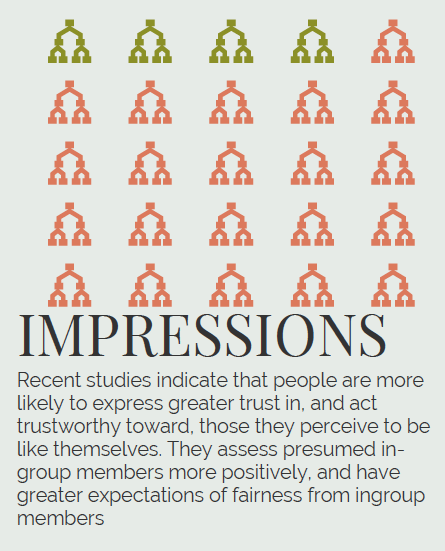

At the same time that the early pharmacies were opening in Fairbanks, the field of “community health” was really taking hold in many locations in the Western world. Community health is the idea that the health of the whole community can be maintained by each member of that community doing their part (such as isolating if you know you have an infectious disease). One profession that came out of the idea of community health was the Public Health Nurse. The first Public Health Nurses were working in New York in the 1890’s. In Alaska, there were eleven Public Health Nurses working for the Department of Health and Social Services by 1938.

The advent of the professional position of “Public Health Nurse” was a big step in making health care more accessible. The Public Health Nurse (PHN) went into the community to see their patients, instead of requiring patients to travel from their community. Because they went to their patients, they were able to directly interact with people who were unable (or unlikely) to go to a larger health center, such as a clinic. However, this also meant that they had to work under the assumption that they would be providing medical care alone. This is similar to the assumption surrounding the Klondike Medicine Chest. Unlike the Klondike Medicine Chest, which was primarily intended for a self-administration, the contents of the Public Health Nurse’s bag were assembled for use by a trained medical professional working with patients.

A PHN was often the primary medical professional that members of their community interacted with. PHN’s had many duties: they provided care for a range of illnesses and conditions, were often the first Western medical professional to see a baby after they were born, provided education regarding Western concepts of cleanliness and hygiene, and did prophylactic examinations of adults, children, and infants. Through the education and care they provided, Public Health Nurses were major contributors to maintaining the health of a community. In many areas of the world, Public Health Nurses increased the life expectancy and decreased the disease load of the communities they served. Today, there are still Public Health Nurses working in Alaska and all over the world.

All the items in this post can be viewed at the UAF Rasmuson Library, 4th floor exhibit case. Detailed records are viewable online in our collection database here: https://arctos.database.museum/saved/Loan202234EH