The Seattle Sunday Times, Oct. 16, 1910

“FAIRBANKS MEN SEND TAFT MASTODON TUSK — A section of mastodon tusk twenty-five inches long, crusted with bas-reliefs wrought in unalloyed Alaska gold that form an epitome of gold mining in the Interior North, is an heroically proportioned desk ornament citizens of the Tanana Valley are sending to President W.H. Taft. This presentation is intended to mark the recent visit to Fairbanks of Secretary of Commerce and Labor Charles Nagel and Attorney-General George Wickersham, personally representing the chief executive. While the cabinet officials were at Fairbanks they were lavishly entertained, and became popular. At a big reception one evening, the suggestion was made by a wealthy mine owner that a symbolical souvenir be sent to President Taft as a token of appreciation.”

So begins the Seattle Times article about what would come to be known as “The Taft Tusk.” According to the article, J.L. Sale, a jeweler called “the Tiffany of the North” was to produce “the most elaborate memento ever sent out of Alaska.” When the Times interviewed Sales about the tusk, he said “It is simply a great piece of mastodon ivory, mounted with gold. The ivory was dug from a mine, where the tusk had lain for hundreds of years. It is a beautiful piece. It’s striking characteristics of color being brought out effectively by polishing.” Presumably President Taft received the tusk and the people of Fairbanks were satisfied that they had represented our community and our economy.

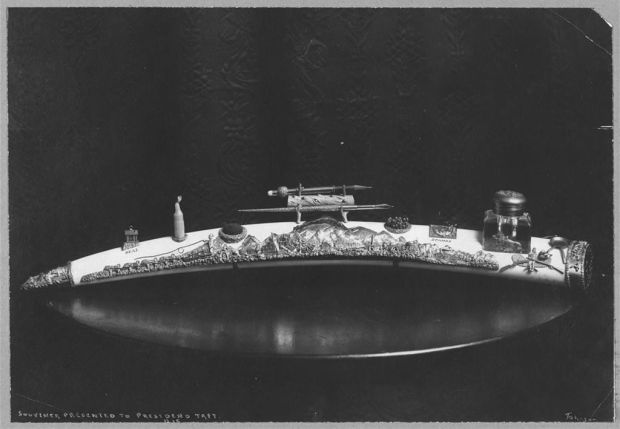

Ivory tusk of a walrus which was carved by an Eskimo and presented to President Taft. Alaska United States, ca. 1900. [Between and Ca. 1930] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/99614746/. (Accessed July 28, 2017.)

Through a cordial series of communications, the Taft children purchased the desk set back from the gallery and donated it to the University Museum in Fairbanks, in order to be exhibited with a short history of the presentation by the people of Fairbanks to President Taft. The desk set arrived in Fairbanks and promptly went on exhibit in a glass case, where it was “quite the center of attraction. Our mining men are greatly interested in this work of art,” according to President Charles Bunnell, who received the gift. A story appeared in the August 1, 1944 copy of the Farthest-North Collegian (p. 6). It’s here where the first inconsistency appears.

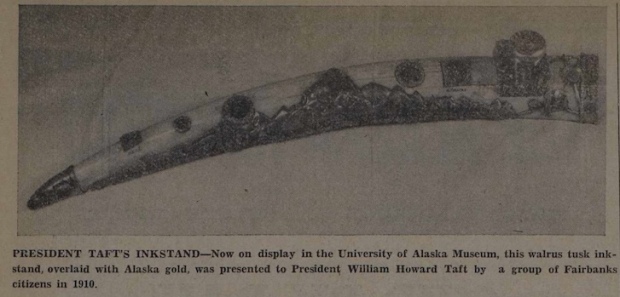

The Farthest-North Collegian, August 1, 1944, page 6.

The caption and headline of the article describes the tusk as being made from a “walrus tusk” while the original 1910 article from the Seattle Times clearly identifies the tusk as mastodon. This early photograph shows the details on the piece. One particular image does made it appear to be walrus ivory, though it is often impossible to tell the difference without close examination.

Detail of tusk (catalog number 0267-4176) and gold overlay. Notice the mottled appearance of the ivory to the left of the mountain. This may confirm the tusk as being made from walrus, not mastodon, ivory. UAMN Photo.

The tusk remained in its place of honor in the museum for many years, appreciated by visitors and student alike. The beginning of another controversy began to bubble to the surface sometime in the 1960s. In a 1968 article of Jessen’s Daily (Wednesday, Mar. 27, 1968, p. 9) Harry Avakoff describes his career as a jeweler in Fairbanks, counting as one of his major accomplishments as being “commissioned by Tanana Valley citizens to make a gold inkwell for President Taft.”

Then, on the morning of April 8, 1969, University of Alaska Museum Director Lu Rowinski opened the museum at 8:00 am and discovered the tusk had been stolen. A $100 reward was offered for information leading to the return of the tusk, “no questions asked,” according to the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner article. People at the time were concerned that the thief would melt down the gold in order to sell it more quickly.

A search of online newspaper articles reveals that only months later, Andrew Hehlin was arrested after the Alaska State Troopers recovered five car loads of stolen property, which included the gold figurines from the desk set, but not the ivory tusk. According to Glen Simpson, who was then a faculty member in the UAF art department and commissioned to repair the desk set in 1973, the museum had acquired a large number of walrus tusks from Barrow, thinking one might have the right contours to match the gold overlay. However, no tusk could be found and so instead, Simpson carved a replacement tusk of walnut. The desk set was returned to the museum and was included in the July 27, 1973 opening of the C.J. Berry Gold Room.

One might think this was the end of the story. The tusk was back on exhibit for the public to enjoy. However, there remained, even until 1999, some disagreements regarding the true artist responsible for the design and fabrication of the tusk: J.L. Sale or Harry Avakoff. Avakoff was quoted in a number of newspaper articles on file at the museum, that one of his life’s greatest accomplishments was being commissioned to make the tusk. In 1983, Emily Avakoff, Harry’s widow, visited the director of the museum and expressed her concern that the tusk label did not credit her late husband as the artist. A number of letters and supporting documentation was exchanged, and a pair of hand-written notes with no dates indicate that “Jack Sale” made the tusk, owned the Fairbanks jewelry store where Avakoff, as well as Vic Brown, were employed. “He did some work on the tusk,” says one note, indicating that both men were associated with the fabrication of the work of art.

In the end, the museum records cite both men as the creators of the desk set, as well as Glen Simpson. The piece has been on continuous exhibit, with the exception of the brief hiatus between 1969-1973, since its 1944 donation and forms the centerpiece of our gold case in the Gallery of Alaska. You can see the catalog record and some of those records in our museum database here.

As part of our Gallery of Alaska renovation project, the gold case was opened for photography and cleaning. Here I am removing the Taft Tusk from its mount. UAF Photo by Todd Paris.