(Taking advantage of some brain power of one of my graduate student curatorial assistants, this posting is written by Kirsten Olson of UAF. William Yanert is one of the most intriguing “characters” of Interior Alaska history and the subject of numerous inquiries to our department. This is a condensed version of a paper Kirsten wrote for an art history course at UAF.)

It was late in the evening when I was working in the range, putting away a cannon ball in one of the larger cabinets when I found myself nose to nose with a large carved devils head! It had strikingly green cat-like eyes, a black painted face with two red stripes on both cheeks, and needless to say, scared the pants off me! Once I recovered from the initial scare, I went back to lab and checked the database to learn more about the terrifying head I encountered.

I discovered that it was the creation of William Yanert, an early Alaskan pioneer. After further research, I had become intrigued by his devil’s head and other carvings in the collection. During the spring semester, I was given an opportunity in an art history class to do more in-depth research on William Yanert, employing the museum’s collection of his work.

Yanert was born in Olschyna, Prussia on March 3rd 1864 and immigrated to the US around 1881 and shortly after enlisted in the U. S. Army. While in the army, Yanert served with the Fifth and Sixth Calvary in the Indian Wars, trained in cartography, and was dispatched in 1897 as a member of Capt. Edwin Glenn’s Alaska Exploring Expedition, scouting and reporting on the conditions between Skagway to Lake Bennett (later this trail became the Chilkoot Trail of the 1898 gold rush). He was assigned to map the Haines Mission and surrounding country, various tributaries of Susitna River, as well as reporting on and mapping the Healy and Talkeetna Mountain area. As a civil engineer, he mapped regions of McKinley Park and Dyea area. He was also the first man to explore Broad Pass, where the Alaska Railroad runs through.

Yanert was born in Olschyna, Prussia on March 3rd 1864 and immigrated to the US around 1881 and shortly after enlisted in the U. S. Army. While in the army, Yanert served with the Fifth and Sixth Calvary in the Indian Wars, trained in cartography, and was dispatched in 1897 as a member of Capt. Edwin Glenn’s Alaska Exploring Expedition, scouting and reporting on the conditions between Skagway to Lake Bennett (later this trail became the Chilkoot Trail of the 1898 gold rush). He was assigned to map the Haines Mission and surrounding country, various tributaries of Susitna River, as well as reporting on and mapping the Healy and Talkeetna Mountain area. As a civil engineer, he mapped regions of McKinley Park and Dyea area. He was also the first man to explore Broad Pass, where the Alaska Railroad runs through.

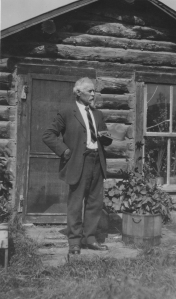

Herman (Left) and William (Right) Yanert standing outside of their cabin on the Yukon; with moose antlers hung over the door and a carved sign that read, “Search not the world for happiness, You’ll find her not on land or sea, no use looking for her address, for she lives right here with me”.

St. Nicolas was carved from a birch burl, with horns, green bottle eyes, and red cape draped around his shoulders.

After his army career, Yanert retired in 1903 and was determined to make his place amidst the land he had come to love so much. He built a cabin and named the land in the Yukon Flats he claimed “Purgatory“, because it was “one hell of a place to live”. A few years later, William’s brother, Herman, came to join him.

Over the years, the brothers had developed quite the reputation for peevishness. Steamboats, carrying tourists, had stopped at Purgatory to stock up on wood, Alaskan hospitality and the Yanerts’ practical jokes. This included the devil’s head that I had stumbled upon. The “devil” was named St. Nicolas, and dubbed the Patron Saint of Purgatory. William had him wired to the cabin so that he could wave “hello” or “goodbye” to those passing by on the Yukon. Other devils and imps were carved out of the burls from birch trees and rigged up like jack-in-the-boxes.

Anyone coming down the river was welcomed at Purgatory by St. Nicholas and the brothers, even unexpected guests such as the Evancoe brothers, who in 1937, were floating down the Yukon River. According to a letter Paul Evancoe wrote to the museum in 1976, he recalled that they had fallen asleep, and were “awakened by a gruff voice, ‘Why the hell don’t you fellas come up to the cabin?’…so we pulled our kayak ashore and proceeded to the Yanert cabin situated back a short distance from the river bank…Well, we spend three of the most delightful days as their guests. Inside their cabin were shelves of carvings that they made of wood, ivory, and bone.”

“The Stampeeder” Yanert used whatever materials he had available to him, including cigar boxes.

Catalog number 0768-0038

William would carve and paint a range of characters, including those from Shakespearian plays such as Othello, Desdemona, and Yorick as well as scenes of the people who lived in Alaska; mushers, natives, hunters, and gold miners. These images were often done on cigar boxes that had been repurposed as a painting board of sorts.

He also carved figures from moose or caribou antlers. The carvings, inspired by the pioneer life he lived, also reflected his philosophy on life, which would often accompany his work in title form, or with a snippet of poetry that was incorporated into the work. Later, he published a collection of his poems, titled Yukon Breezes, accompanied by his hand colored illustrations.

They spent their lives surviving off of and surrounded by their hard work. Their cabin at Purgatory was filled with handmade furniture and decorated with carvings. The front of the cabin was bedecked with totems, some more than twenty feet high. In the 40 years he lived there, he only left once, when his health took a turn for the worse in the fall of 1941 and a year later, he passed away.

The majority of his works, carvings, paintings, photographs, and a copy of his poem, Yukon Breezes, were donated to the University of Alaska Museum of the North by Ralph Newcomb and Herman Yanert in 1943. The collection in the museum is just a snippet of what was once the glorious and remarkable Purgatory. We can sill enjoy the humor and sincerity of William’s artwork in these items held by the University of Alaska Museum of the North, as well as the writings and photographs of the Yanerts in the Alaska and Polar Regions Collections and Archives at the Elmer. E. Rasmuson Library here, at UAF.